Eastern Kingbird

General Description

The Eastern Kingbird is gray-black above and white below. Its most distinctive field mark is the white band at the tip of its black tail. Like other flycatchers it maintains an upright posture. It has a small patch of red feathers in its crown that can only be seen when it displays.

Habitat

In Washington, Eastern Kingbirds forage in habitat similar to that of Western Kingbirds, open shrub-steppe and agricultural areas. Their breeding habitat, however, is quite different. They nest in hardwood stands, almost always on or near rivers, streams, or other wetlands. Because of their different foraging and breeding habitats, they are commonly found at edges where these habitats meet.

Behavior

During the breeding season, Eastern Kingbirds typically do not flock, but during migration and on the wintering grounds, they gather in large groups. They generally forage in short bursts, flying out from the perch to grab prey in mid-air, and then returning to the same spot. They also glean prey from foliage or pick food items off the ground, especially in cooler weather when many insects don't fly. These aggressive flycatchers can often be seen perched on a fence wire or treetop, or flying with wings fluttering downward.

Diet

In spring and summer Eastern Kingbirds eat mostly insects. As the summer progresses, they eat more and more fruit. On the wintering grounds they eat primarily berries.

Nesting

During courtship the male performs elaborate display flights. Monogamous pairs will often re-pair in successive years and reclaim the same territory. The female builds the nest in a low deciduous tree or shrub, on a utility tower, or in a tree growing out of the water. The nest is large and bulky, made of weeds, bark, and twigs, and lined with plant down, hair, and feathers. The female incubates the two to five eggs for 14 to 17 days. Both parents feed the young, which leave the nest and take their first flights at 16 to 18 days. The parents continue to feed the young for another three to five weeks after they fledge.

Migration Status

As their name implies, Eastern Kingbirds are historically a bird of the eastern part of the US, and their migration patterns trace their westward expansion. Eastern Kingbirds arrive in Washington by late May, from the east, making them one of Washington's latest spring migrants. They begin to leave in August, with the last few remaining until September. They head east over the Rocky Mountains and travel south to South America from there. They travel in flocks and migrate by day as far south as Argentina.

Conservation Status

Although development and conversion of small farms to more intensive agriculture with fewer shelterbelts have reduced nesting habitat for Eastern Kingbirds, its population in Washington has been stable between 1966 and 2002. Maintaining shelterbelts and forested corridors along streams is necessary to protect Eastern Kingbird habitat in Washington.

When and Where to Find in Washington

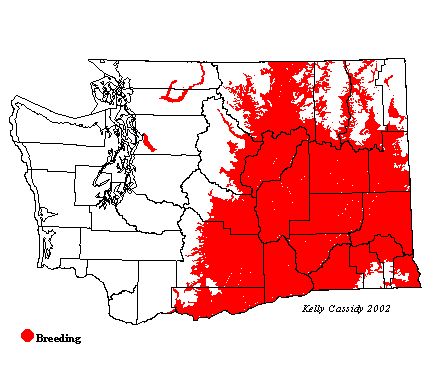

Mostly an eastern Washington species, the Eastern Kingbird breeds in a few areas in Western Washington--in Pierce, Snohomish, and Skagit Counties. In eastern Washington they are common throughout the shrub-steppe region near lakes, ponds, marshes, and farmland.

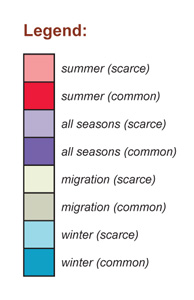

Abundance

Abundance

| Ecoregion | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oceanic | ||||||||||||

| Pacific Northwest Coast | ||||||||||||

| Puget Trough | R | R | R | R | ||||||||

| North Cascades | R | R | R | R | ||||||||

| West Cascades | ||||||||||||

| East Cascades | R | U | U | U | R | |||||||

| Okanogan | U | C | C | C | U | |||||||

| Canadian Rockies | F | F | F | F | U | |||||||

| Blue Mountains | U | U | U | U | ||||||||

| Columbia Plateau | F | C | C | C | R |

Washington Range Map

North American Range Map

Family Members

Olive-sided FlycatcherContopus cooperi

Olive-sided FlycatcherContopus cooperi Western Wood-PeweeContopus sordidulus

Western Wood-PeweeContopus sordidulus Alder FlycatcherEmpidonax alnorum

Alder FlycatcherEmpidonax alnorum Willow FlycatcherEmpidonax traillii

Willow FlycatcherEmpidonax traillii Least FlycatcherEmpidonax minimus

Least FlycatcherEmpidonax minimus Hammond's FlycatcherEmpidonax hammondii

Hammond's FlycatcherEmpidonax hammondii Gray FlycatcherEmpidonax wrightii

Gray FlycatcherEmpidonax wrightii Dusky FlycatcherEmpidonax oberholseri

Dusky FlycatcherEmpidonax oberholseri Western FlycatcherEmpidonax difficilis

Western FlycatcherEmpidonax difficilis Black PhoebeSayornis nigricans

Black PhoebeSayornis nigricans Eastern PhoebeSayornis phoebe

Eastern PhoebeSayornis phoebe Say's PhoebeSayornis saya

Say's PhoebeSayornis saya Vermilion FlycatcherPyrocephalus rubinus

Vermilion FlycatcherPyrocephalus rubinus Ash-throated FlycatcherMyiarchus cinerascens

Ash-throated FlycatcherMyiarchus cinerascens Tropical KingbirdTyrannus melancholicus

Tropical KingbirdTyrannus melancholicus Western KingbirdTyrannus verticalis

Western KingbirdTyrannus verticalis Eastern KingbirdTyrannus tyrannus

Eastern KingbirdTyrannus tyrannus Scissor-tailed FlycatcherTyrannus forficatus

Scissor-tailed FlycatcherTyrannus forficatus Fork-tailed FlycatcherTyrannus savana

Fork-tailed FlycatcherTyrannus savana