Cackling Goose

General Description

Note: Based on differences in size, voice, breeding habitat and genetics, the American Ornithologists' Union has split Canada Goose into two species, Canada Goose (Branta canadensis) and Cackling Goose (Branta hutchinsii). Of the eleven sub-species previously grouped under Canada Goose, the four smaller-bodied, tundra-breeding subspecies have been re-classified as Cackling Goose.

Cackling Geese appear almost identical to Canada Geese: mottled gray-brown body, black legs, tail, neck, head and face, with a white chin strap stretching from ear to ear and a white rump band. Like Canada Geese, some Cackling Geese show a white collar at the base of the neck and/or a black chin-stripe dividing the white cheek patches. Cackling Geese are best distinguished from Canada Geese by overall body size, bill shape and size, and voice.

Cackling Geese are generally smaller than Canada Geese, although overlap in size between the larger subspecies of Cackling Geese and the smaller subspecies of Canada Geese can make identification by size alone difficult. The smallest Cackling Geese weigh about 3 to 4 lbs. (a little larger than a mallard) with the largest subspecies weighing as much as 7 lbs., whereas Canada Geese range in size from 5 to 15 lbs. Compared to Canada Geese, Cackling Geese have proportionally smaller, stubbier bills and higher-pitched voices.

Length of neck in flight can be a useful indicator of species (shorter for Cackling Geese, longer for Canada Geese); however, because geese can elongate or retract their necks, neck length can be difficult to determine in swimming or sitting birds. Due to their smaller size, Cackling Geese (especially B.h. minima) display a faster wingbeat than Canada Geese and their wings appear longer proportionally to their body size in flight.

Cackling Geese do not show any seasonal variation and sexes are alike, although males are slightly larger.

Habitat

On their tundra breeding grounds, Cackling Geese are always found near water. In winter and during migration they are found on inland lakes, rivers and marshes; in coastal salt marshes, bays and tidal flats; in brackish ponds, pastures and agricultural fields, and in grassy fields in urban and suburban parks with close proximity to water.

Behavior

Cackling Geese are primarily herbivores. The hard nail on their bill makes them efficient at grazing on grasses and plants while their long necks and the ability to tip-up enables them to forage on submerged aquatic plants. During migration and winter, Cackling Geese are highly gregarious, feeding in large flocks; individuals and family groupings are often found in flocks with Canada Geese. Cackling Geese become less gregarious with the approach of the breeding season as pairs leave the flock in search of nest sites. During the breeding season, they maintain their territory by threats and fights.

Cackling Geese are strong swimmers, walkers, and fliers; they rest standing on one or both legs and often sleep on water, forming rafts.

Diet

On their tundra breeding grounds, Cackling Geese forage primarily on grasses, sedges, and berries. Prior to fall migration, they shift their diet to include higher amounts of sedge seeds and berries in order to gain fat. In wintering areas, Cackling Geese forage on grasses and agricultural crops, including winter wheat, alfalfa and barley.

Nesting

Cackling Geese are generally monogamous, forming life-long pair bonds during their second year (they may form a new pair bond with the loss of a mate). The various subspecies return to their traditional breeding areas year after year. The female selects the nest site, generally a slightly elevated location with good visibility near the edge of a pond or stream, on a small island in a pond or stream, or along the arctic coastal plain. One subspecies (B.h. leucopareia) breeds on steep slopes and cliff edges on fox-free islands in the Aleutians. Reuse of old nest sites is frequent. The nest is constructed of material available at the site (sedges, lichens, mosses) and feathers. The female incubates the eggs (generally 4-5) while the male stands guard.

Goslings are precocial and leave the nest within 24 hours of hatching, at which time they are able to walk, swim, dive and feed. The parents lead the brood to grazing areas but do not feed them. The young fledge approximately 6-7 weeks after hatching. The young leave the breeding areas with their parents and may remain with them throughout the first winter.

Migration Status

Cackling Geese are long-distance migrants, following relatively direct, traditional flight paths between their breeding grounds in the arctic and their wintering grounds in the Pacific Northwest, California, and the gulf coast of Texas. Spring migration can begin as early as late January and is prolonged by stops at traditional sites to replenish nutrients before arriving at the breeding grounds. Fall migration begins in late August and can be non-stop or interrupted. Cackling Geese may reverse migration and return to a previous stop along the route if they encounter unfavorable weather.

Migrating flocks are comprised of family groups and individuals. Flocks are variable in size, depending on the subspecies and usually fly in a V formation. Flights usually begin at dusk but may occur at any time of the day. Migrating flocks generally fly at low elevation (300-1000 meters) and often maintain speeds of over 50 kilometers per hour for extended periods.

In winter, Cackling Geese subspecies often flock together and also mix with Canada Geese.

Conservation Status

Cackling Geese are classed as migratory game birds and, together with Canada Geese, are among the top waterfowl harvested in the US and Canada. The conservation and management of Cackling Geese involves achieving a balance between too few geese and too many geese, and maintaining diversity of subspecies. In Washington, one subspecies of Cackling Goose is increasing (B.h. taverneri), one is declining (B.h. minima), and a third is recovering after a decline (B.h. leucopareia).

Cackling Geese are susceptible to lead poisoning from ingesting lead pellets in hunting areas and mortality from pesticides and other toxins. The decline in numbers of B.h. minima may be due to sport and subsistence hunting. Gas and oil development in the arctic may put some populations of Cackling Geese at risk.

Because all Canada Geese and Cackling Geese subspecies look generally alike, hunters must be educated to recognize the Aleutian Cackling Goose (B.h. leucopareia), which is a protected subspecies. Identification difficulties make it difficult to get accurate population totals of Cackling Geese.

When and Where to Find in Washington

Migrants begin to arrive in Washington in late August but larger numbers of Cackling Geese arrive in late September, peaking from late October through late November. Spring migration begins in late February, peaking in March through April; stragglers can be found into late May.

On the east side of the Cascades, Cackling Geese are uncommon. When found, they use agricultural areas and small lakes in the Columbia basin, especially Grant and Adams counties; sometimes lingering in the fields north of the Para Ponds (near Othello) during their spring migration. In western Washington, migrants are mostly found along the outer coast although some come through the Puget Sound during fall migration, and wintering Cackling Geese are found along the Columbia River from Vancouver to Ilwaco and around Willapa Bay and Grayâ??s Harbor. Good places to look for wintering Cackling Geese in western Washington include Willapa National Wildlife Refuge (Pacific County), Julia Butler Hansen National Wildlife Refuge (Wahkiakum County) and Ridgefield National Wildlife Refuge (Clark County).

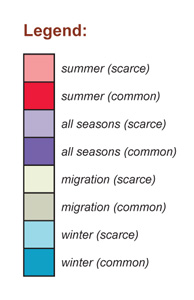

Abundance

Abundance

| Ecoregion | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oceanic | ||||||||||||

| Pacific Northwest Coast | F | F | F | F | F | F | F | F | F | |||

| Puget Trough | C | C | C | C | U | U | C | C | C | |||

| North Cascades | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | ||||

| West Cascades | F | F | F | F | F | F | F | |||||

| East Cascades | U | F | F | U | R | F | F | U | ||||

| Okanogan | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | |||||

| Canadian Rockies | ||||||||||||

| Blue Mountains | ||||||||||||

| Columbia Plateau | F | F | F | U | U | F | F |

North American Range Map

Family Members

Fulvous Whistling-DuckDendrocygna bicolor

Fulvous Whistling-DuckDendrocygna bicolor Taiga Bean-GooseAnser fabalis

Taiga Bean-GooseAnser fabalis Greater White-fronted GooseAnser albifrons

Greater White-fronted GooseAnser albifrons Emperor GooseChen canagica

Emperor GooseChen canagica Snow GooseChen caerulescens

Snow GooseChen caerulescens Ross's GooseChen rossii

Ross's GooseChen rossii BrantBranta bernicla

BrantBranta bernicla Cackling GooseBranta hutchinsii

Cackling GooseBranta hutchinsii Canada GooseBranta canadensis

Canada GooseBranta canadensis Mute SwanCygnus olor

Mute SwanCygnus olor Trumpeter SwanCygnus buccinator

Trumpeter SwanCygnus buccinator Tundra SwanCygnus columbianus

Tundra SwanCygnus columbianus Wood DuckAix sponsa

Wood DuckAix sponsa GadwallAnas strepera

GadwallAnas strepera Falcated DuckAnas falcata

Falcated DuckAnas falcata Eurasian WigeonAnas penelope

Eurasian WigeonAnas penelope American WigeonAnas americana

American WigeonAnas americana American Black DuckAnas rubripes

American Black DuckAnas rubripes MallardAnas platyrhynchos

MallardAnas platyrhynchos Blue-winged TealAnas discors

Blue-winged TealAnas discors Cinnamon TealAnas cyanoptera

Cinnamon TealAnas cyanoptera Northern ShovelerAnas clypeata

Northern ShovelerAnas clypeata Northern PintailAnas acuta

Northern PintailAnas acuta GarganeyAnas querquedula

GarganeyAnas querquedula Baikal TealAnas formosa

Baikal TealAnas formosa Green-winged TealAnas crecca

Green-winged TealAnas crecca CanvasbackAythya valisineria

CanvasbackAythya valisineria RedheadAythya americana

RedheadAythya americana Ring-necked DuckAythya collaris

Ring-necked DuckAythya collaris Tufted DuckAythya fuligula

Tufted DuckAythya fuligula Greater ScaupAythya marila

Greater ScaupAythya marila Lesser ScaupAythya affinis

Lesser ScaupAythya affinis Steller's EiderPolysticta stelleri

Steller's EiderPolysticta stelleri King EiderSomateria spectabilis

King EiderSomateria spectabilis Common EiderSomateria mollissima

Common EiderSomateria mollissima Harlequin DuckHistrionicus histrionicus

Harlequin DuckHistrionicus histrionicus Surf ScoterMelanitta perspicillata

Surf ScoterMelanitta perspicillata White-winged ScoterMelanitta fusca

White-winged ScoterMelanitta fusca Black ScoterMelanitta nigra

Black ScoterMelanitta nigra Long-tailed DuckClangula hyemalis

Long-tailed DuckClangula hyemalis BuffleheadBucephala albeola

BuffleheadBucephala albeola Common GoldeneyeBucephala clangula

Common GoldeneyeBucephala clangula Barrow's GoldeneyeBucephala islandica

Barrow's GoldeneyeBucephala islandica SmewMergellus albellus

SmewMergellus albellus Hooded MerganserLophodytes cucullatus

Hooded MerganserLophodytes cucullatus Common MerganserMergus merganser

Common MerganserMergus merganser Red-breasted MerganserMergus serrator

Red-breasted MerganserMergus serrator Ruddy DuckOxyura jamaicensis

Ruddy DuckOxyura jamaicensis